“A labourer over the course of an 8-hour day can sustain an average output of about 75 watts”

(Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers)

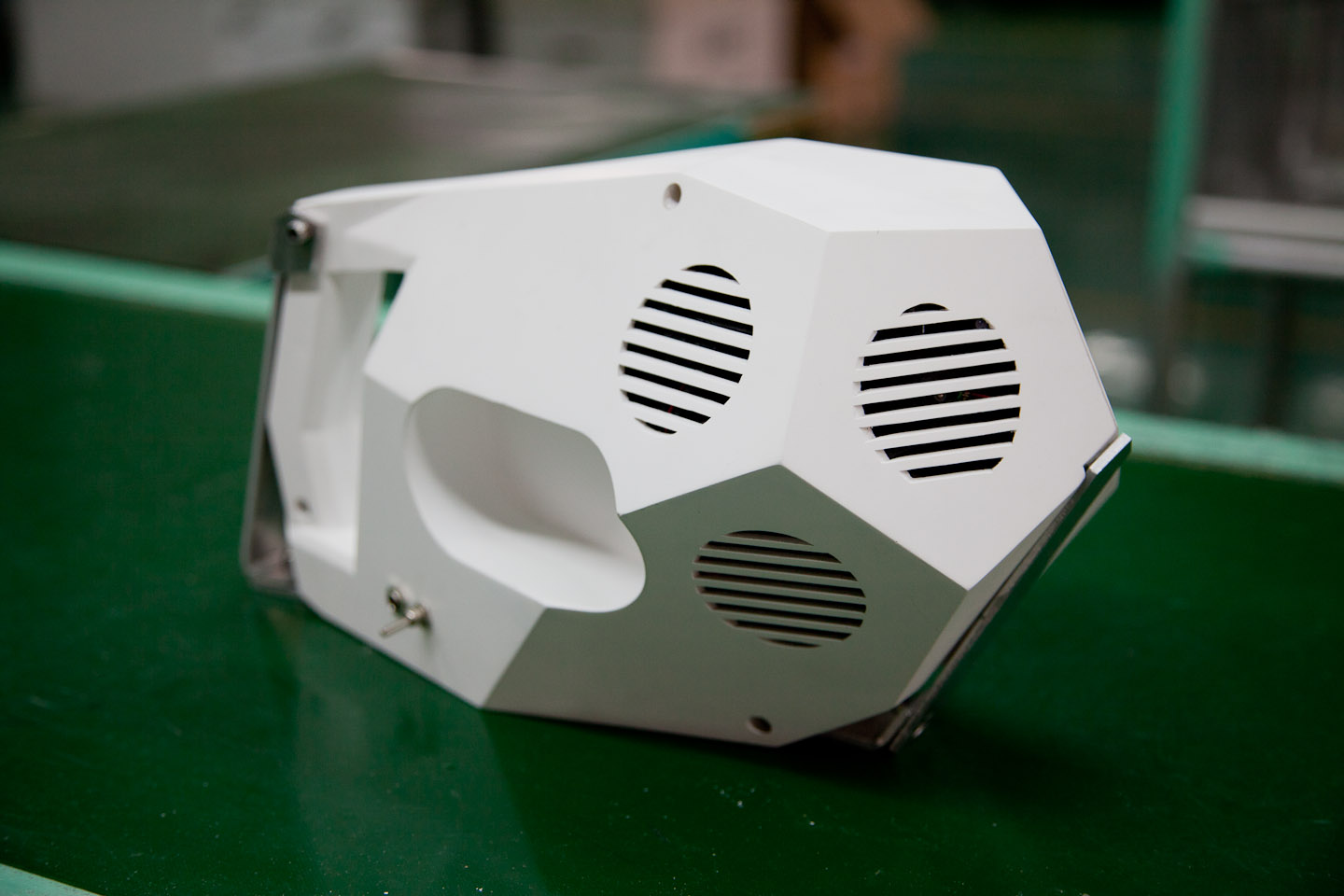

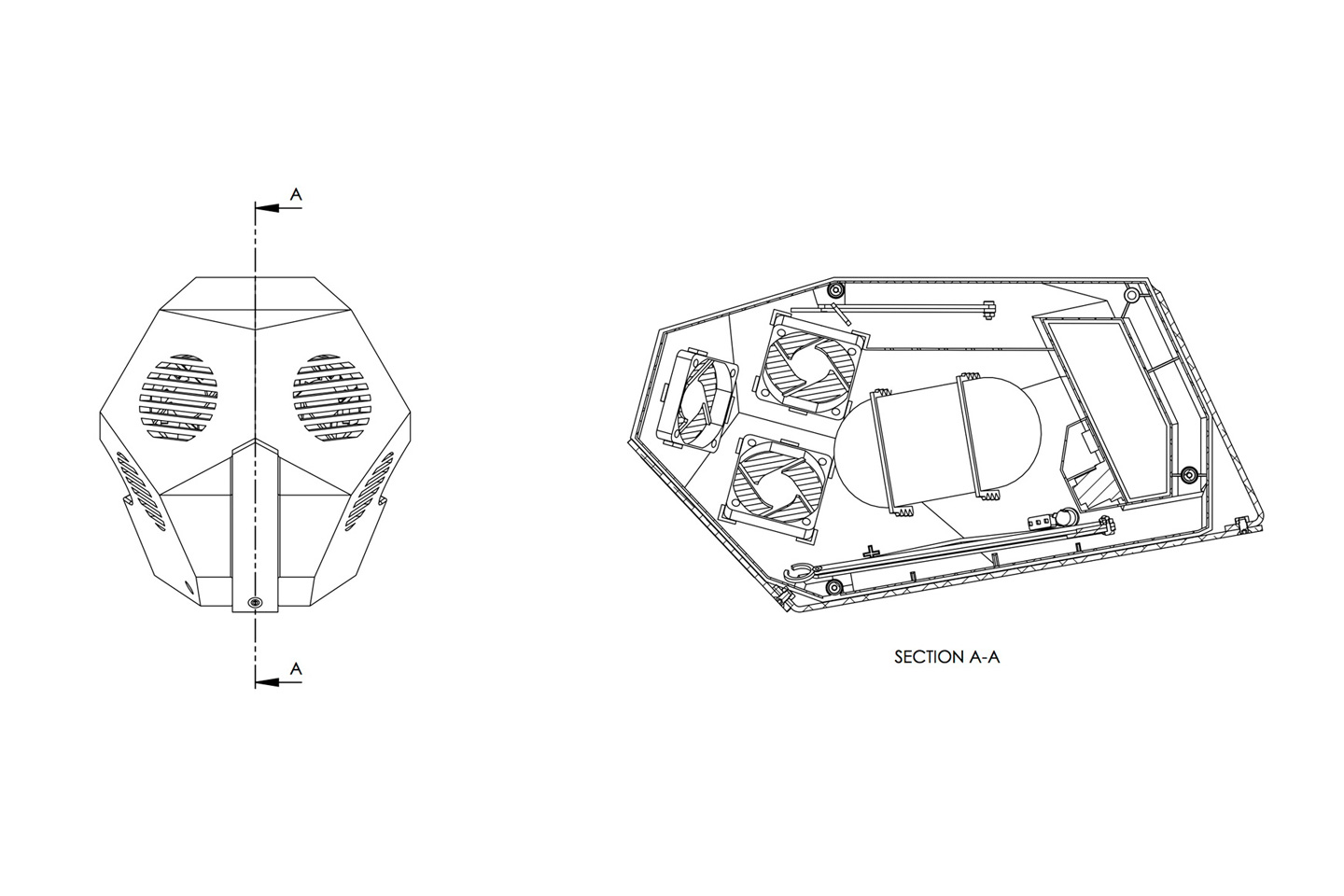

In 75 Watt, a product is designed to be made in China. The object’s only function is to choreograph a dance performed by the labourers manufacturing it.

The work seeks to explore the nature of mass-manufacturing products on various scales; from the geo-political context of hyper-fragmented labour to the bio-political condition of the human body on the assembly line. Engineering logic has reduced the factory labourer to a man-machine, through scientific management of every single movement. By shifting the purpose of the labourer’s actions from the efficient production of objects to the performance of choreographed acts, mechanical movement is reinterpreted into dance. What is the value of this artefact that only exists to support the performance of its own creation? And as the product dictates the movement, does it become the subject, rendering the worker the object?

The assembly/dance took place at the White Horse Electric Factory in Zhongshan, China between 10-19 March 2013 and resulted in 40 objects and a film documenting the choreography of their assembly.

> Choreography: Alexander Whitley

> Line producer: Siya Chen

> Supported by:

Arts Council England, Flemish Authorities, Ask4Me Group, Zhongshan City White Horse Electric Company, FACT, V2_Institute for the Unstable Media, workspacebrussels

> Thanks to:

Yang QiCong, Lin Jun Xiong, Brittany Galpin, Selina Glockner, Simon Donnellon, Megan Rodger, Macon Hang, Pieter Klingels, Evonne Mackenzie, Susan Luoxiaojian, Bart Bakkum, Lisa Ma, Gert Maass

> Collections:

Permanent collection, MoMA, New York

M+ Museum, Hong Kong

.

About halfway down the assembly line, a young female worker carefully weaves an electroluminescent wire through the product. As her hands move on to the next attaching point, the glowing wire traces her motions in the air.

‘Made in China’. Three words that feature on almost every product that plays part in our lives. But despite their ubiquity, very little is known about the real meaning of these words. Why is it that most of us can recite how many megapixels make up the camera on their mobile phone, without knowing how or where the electronic gadget is made? Design and manufacture are political in nature, regardless of the objects produced.

Division of labour has been a predominant force in shaping our civilisation. In modern manufacturing processes however, this very division of labour has been taken to an extreme that perhaps stopped being civilised. Increasingly complex division of labour, hand in hand with design and engineering, have been closely associated throughout history with the growth of total output and trade, the rise of capitalism, and an increasing complexity of industrialisation processes.

Many philosophers, economists and scientists have commented on the division of labour. In the United Kingdom, the 20 pound note reminds the nation of Adam Smith’s “The division of labour in pin manufacturing and the great increase in the quantity of work that results”. Marx on the other hand indicated that division of labour can lead to workers alienation, leaving them “depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine.” But perhaps it is the labourer in the condition of a machine that fits best the engineering logic that underlies and facilitates the increasing complexity of industrialisation processes?

Two workers prepare an electrical cable loom. Using her body to measure different lengths, the first worker indicates where to cut. A second worker makes two cuts and strips back the wire. The finished loom is passed on for soldering.

Engineering logic provides the abstraction and hierarchy that is necessary to design for these increasingly complex industrial processes. The designer/engineer thinks of what he doesn’t (need to) understand as a ‘black box’. When using the right standards, this abstraction allows for the design of ever more complex products in ever more complex processes, resulting in a belief that there is very little we can not engineer. However, it also creates multiple layers of disconnection: disconnection between the designer and maker, disconnection between producers and suppliers, disconnection between technology and people, disconnection between head and pin.

This ‘black box’ logic only works when everything is meticulously characterised: every part in the process must behave in a predictable manner. And within the huge complexity of industrial manufacturing processes, the biological behaviour of human bodies on an assembly line is not always predictable enough to fit within this engineering logic. Even before F.W. Taylor wrote ‘The Principles of Scientific Management’, Frank and Lilian Gilbreth used time lapse photography to study the inefficiencies in workers’ motions. These chronocyclographs were created by attaching a camera to a timing device and photographing workers performing various tasks. The motion paths were traced by small lamps fastened to the worker’s head, hands and fingers.

She picks up half the product’s housing from the assembly line. Holding it by the handle, she shoulders the plastic close to her chin to reach inside and tighten the small bolts that hold the aluminium arms inside.

In 1979, Shenzhen was a fishing village on the shores of the Pearl River with 30 000 inhabitants. It had just become one of China’s special economic zones, a materialisation of Deng Xiaopin’s paradoxical intentions of bringing capitalism into communist China. After 30 years of economic boom, it has an official population around 10 million, and counting. Estimates of its real size sometimes reach double. The city is younger than us and bigger than London. Outsourcing mass manufacturing has created unprecedented urban conditions in the Pearl river delta. And because of Shenzhen’s proximity to other metropoles like Guangzhou, Dongguan and Zhongshan, the whole area might soon merge into a mega city of 85 million people.

The work began with a research trip in September 2011 to study the movements of production. Spending time filming in various factories and assembly plants was an introduction to the culture of ‘made in China’. All parts and components for the final product have also been manufactured in the Pearl River delta. As ever and everywhere with producing, things turn up wrong. However nowhere are these mistakes rectified as quick as in South-East China: parts are remade overnight to arrive next morning through the extensive logistic network of trucks, cars and scooters that drive on and off with raw materials or (half)finished goods. ‘Made in China’ is fast, adventurous and rough around the edges. Like the Wild West in the East, but with manufacturing instead of cowboys.

After attaching the arm to the outside of the object, he tests the joints with a quick succession of movements and places the product back on the assembly line to be packed.

After decades of booming, cheap labour is running out in China’s South-East which means working conditions are improving. Like the cities, workers are often young. The atmosphere in the factories is friendly, relaxed almost. It seems in contrast with the high production volumes, and with western preconceptions. At the same time however, pressure grows on China as the world’s provider of affordable labour. Rising wages in China cause labour-intensive businesses to move to Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia or Vietnam. With rocketing unemployment in the West, criticism grows towards companies that outsource all manufacturing jobs to the dubious social conditions in Asia. Collapsing factories in Bangladesh and reports of suicides due to overworking in companies like Foxconn fuel the concerns. Yet with the products we use and wear every day, we are all part of this systemic violence.

Both East and West look for new manufacturing technologies: from digital manufacturing processes that produce things cheaper, in smaller numbers and with lower input of labour to automated manufacturing lines that replace human workers with robots. The second industrial revolution started when Henry Ford mastered the moving assembly line and ushered in the age of mass production. Now, a third revolution might be underway, bringing to an end the human labourer on the assembly line as we know him. And so we dance to the swan song of the second industrial revolution.