A number of life-support machines are connected to each other, circulating liquids and air in attempt to mimic a biological structure. The Immortal investigates human dependence on electronics, the desire to make machines replicate organisms and our perception of anatomy as reflected by biomedical engineering.

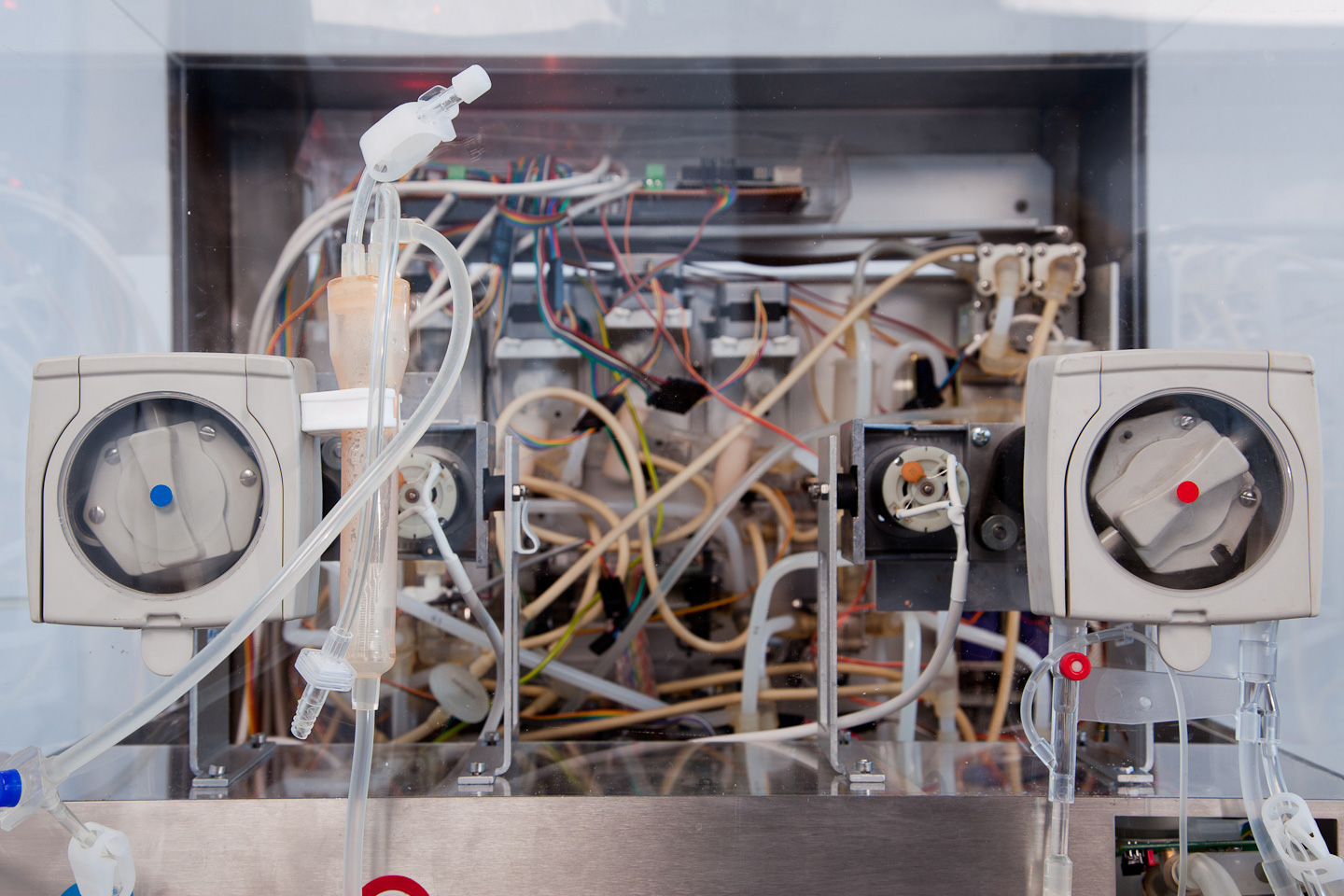

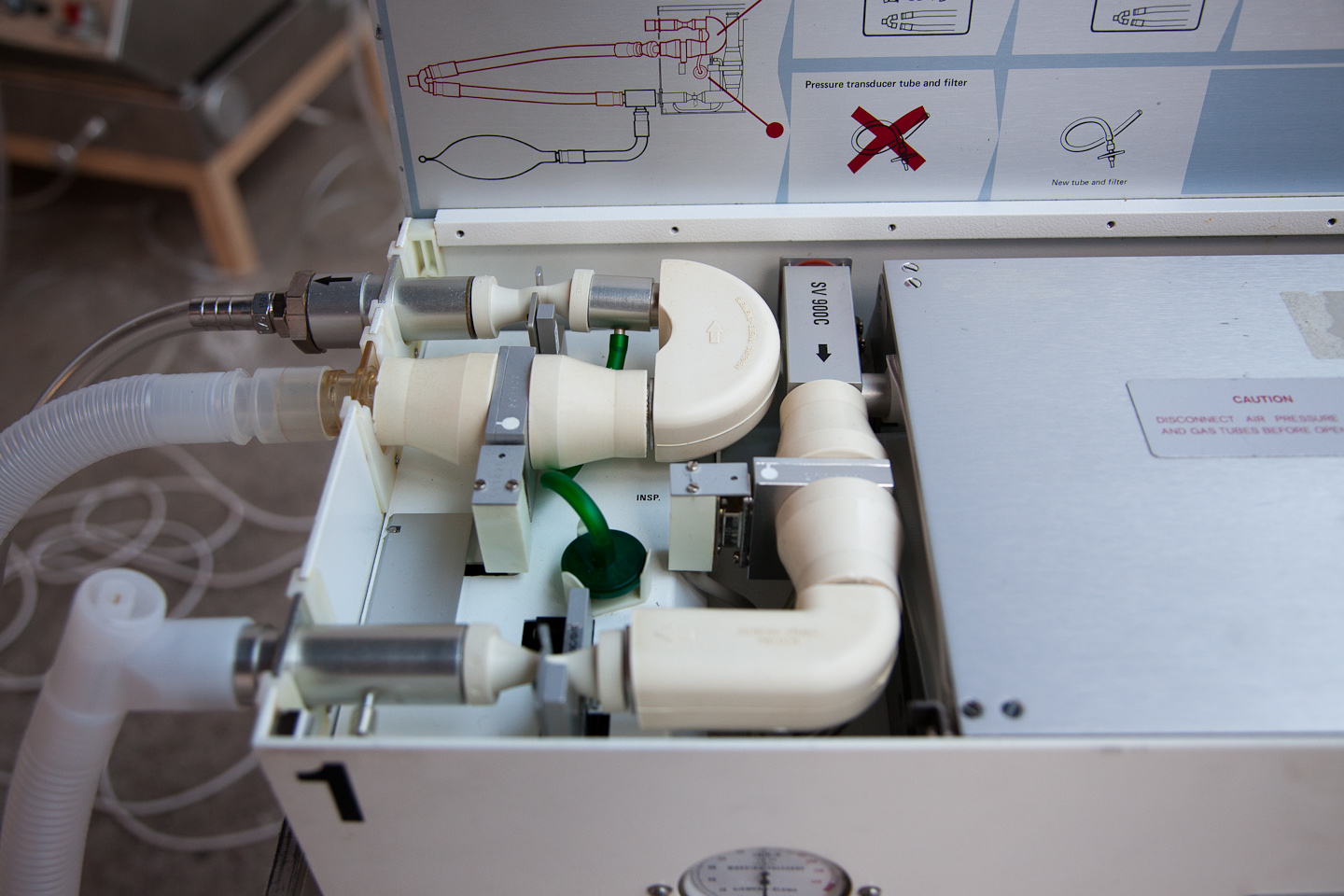

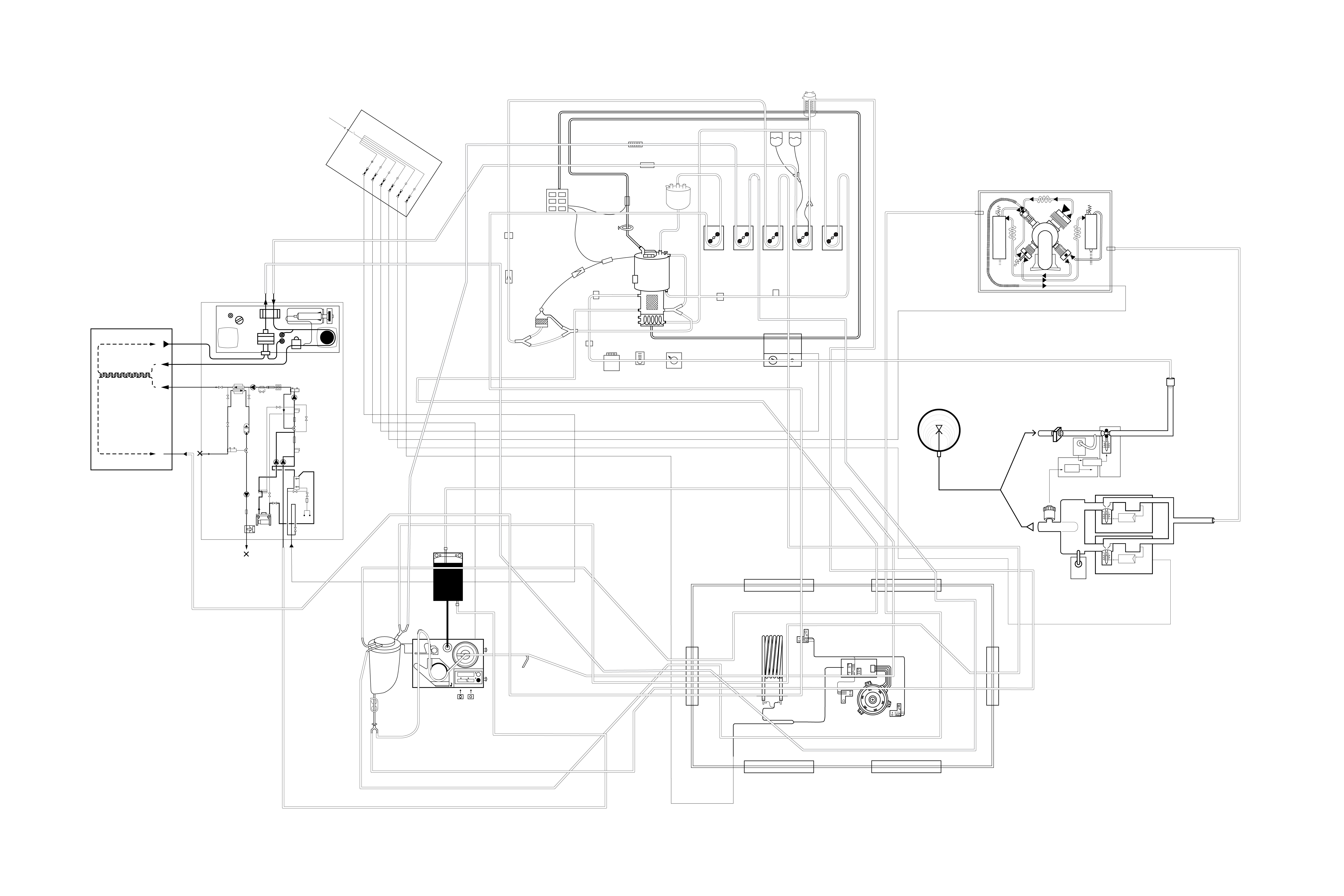

Webs of tubes and electric cords are interwoven in closed circuits through a Heart-Lung Machine, Dialysis Machine, an Infant Incubator, a Mechanical Ventilator and an Intraoperative Cell Salvage Machine. The organ replacement machines operate in orchestrated loops, keeping each other alive through circulation of electrical impulses, oxygen and artificial blood. Salted water acts as blood replacement: throughout the artificial circulatory system minerals are added and filtered out again, the blood gets oxygenated via contact with the oxygen cycle, and an ECG device monitors the system’s heartbeat. As the fluid pumps around the room in a meditative pulse, the sound of mechanical breath and slow humming of motors resonates in the body through a comforting yet disquieting soundscape.

Life support machines are extraordinary devices; computers designed to activate human bodies when anatomy fails, hidden away in hospital wards. Designed as the ultimate utilitarian appliances, they are extremely meaningful and carry a complex social, cultural and ethical subtext. While life prolonging technologies are invented as emergency measures to combat or delay death, the installation considers these devices as a human enhancement strategy.

The work continues our investigations into the idea of the patient as a cyborg, questioning the relationship between medicine and techno- fantasies about mechanical bodies, hyper abilities and posthumanism.

The interpretation of anatomy with a mechanical vocabulary reflects strongly the Western perception of the body. Defining the body as a machine – where dysfunctional parts can be replaced by mechanics – speaks of how we understand our anatomy. These objects encompass social debates about the ethics of euthanasia, the quantification of both the value and quality of life, making physical a poetic desire to conquer our own mortality.

The medical machine – whether in use or not – is an object which transcends its materiality. Designed and created to perform a single, most meaningful function, we never subject these devices to critical investigation as industrial products within the context of material culture. This work aims to explore the nature of these devices as objects of our times, liberated from their restrained purpose while still charged with its resonance.

The installation is the result of an irrational, laborious and ambitious quest – the creation of a Frankenstein- esque system built from advanced medical equipment. Making the machines work without a body required a definition of this creature as its own species – from interpreting mechanical ʻbloodʼ or establishing brain function replacement, to prioritising and mapping functions of cleaning, pumping and oxygenating, in order to construct a coherent circuit. Most of the machines were reconfigured or hacked, “dumbed down” in order to operate without biological matter. All machines were given new casings that expose their inner workings and unify them as organs of the same body.

The collection of machines used in this circuit and the absence of bodily functions that do not exist in mechanical form highlight the way medical technology evolves from culture. The existing technology illustrates the Western view of the lungs and heart as the centre of our being, avoiding confrontation with the digestive system which is conceptually unappealing yet biologically vital. Similarly, the Cell Salvage machine, developed in response to Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal to accept blood transfusions – believed to be in defiance of Godʼs will – is an industrial artefact that blurs the boundary between technocracy and the metaphysical.

Social meanings can also be found within the complex practices and hierarchies surrounding the trade and donation of advanced medical equipment. Medical devices in decline have clear migration patterns: they travel from the western world to the the third world to veterinary practices.

Migration trails indicating which types of machines are in demand in which parts of the world speak of whoʼs body is defined a national priority.

By exploring the medical instruments while detached from the human body and functioning as an independent being, each electronic body part accentuate the distance between the organic and the artificial.

Through the visibility of motors, electronic circuits, fluid pumps, audio-visual signals and particularly the scale and electric exhaustion of the work, we are confronted with the stark contrasts that lie in the primitive functions of precision hardware.

The Immortal is occupied with the compelling and discomforting nature of these objects, the products of our attempts to conquer biology with engineering. The absence of the body only underlines that the machines filling the room are inherently biological.

// Supported by a Wellcome Trust Arts Award

// A special thanks to Marcus Durand, Hans Van Balen, Derek Struthers, Mike Clayton, Steve Fielding, Ian Claydon and Nick Williamson.